Let’s be honest about something most leadership books won’t tell you: you don’t manage priorities at the senior level. You juggle them.

PepsiCo’s former CEO Indra Nooyi once said there’s no such thing as work-life balance, only work-life juggling. The same applies when managing priorities as engineering leader. The more senior you become, the more you realize that the neat frameworks and priority matrices you learned early in your career become almost quaint in the face of organizational reality, and managing priorities as engineering leader just become the act of juggling.

The Illusion Breaks Down

Here’s what a typical Tuesday looks like:

You block out two hours to work on the architecture review for Q4’s flagship initiative. Thirty minutes in, your staff engineer pings you, the vendor integration is broken, and customers are affected. You drop everything.

While you’re in that war room, your phone buzzes. It’s your skip-level 1:1 that you promised you wouldn’t reschedule again. You take it, half your brain still running through incident scenarios.

The incident resolves. You have 20 minutes before your next meeting. You try to context-switch back to the architecture review, but now a team conflict situation has escalated with cross-tribe implications. Not urgent, but ignoring it will make it urgent.

The architecture review? Still incomplete. And the deadline hasn’t moved.

This isn’t poor time management. This isn’t a lack of discipline. This is the job.

Why “Managing” Priority Becomes Impossible

The textbook advice is to categorize everything: urgent-important, important-not-urgent, and so on. Delegate the rest. Sounds perfect.

But here’s what textbooks miss:

Everything actually IS important when you’re accountable for it. That production incident? Important. The architecture decision that affects the next two years? Important. Your engineer who’s struggling and needs guidance? Important. The budget meeting where headcount gets decided? Important.

You can’t Eisenhower-matrix your way out when five “Quadrant 1” items land simultaneously.

Your open door is a priority commitment. You told your team you’re accessible. So when your staff engineer appears at your door with “Do you have five minutes?”, you know it’s never five minutes, and you know it matters. They don’t come to you for trivial things. They come because they’re stuck, or uncertain, or need strategic direction only you can provide.

Saying “not now” is sometimes necessary. But do it too often, and your open door becomes decorative. Your team learns to stop asking. Then you lose visibility into problems until they explode.

The context switching tax is real and invisible. Every switch costs you 15-20 minutes of cognitive reload time. Do that eight times a day, and you’ve lost 2+ hours, not to transition time, but to reduced effectiveness. You’re operating at 60% capacity on everything.

The Context Switching Tax

The Dirty Secret

Here’s what nobody told me until I was years into this role: senior leadership is firefighting. Not every day, but many days. Maybe most days.

You want to be strategic. You want to work “on the business, not in the business.” You want to think long-term and build systems that prevent fires.

And you’ll do some of that. But you’ll also spend Tuesday afternoon debugging why the hiring pipeline dried up, Wednesday morning managing a conflict between two teams over API ownership, and Thursday in an emergency exec review because the numbers shifted.

The people who romanticize “working on the business” either aren’t in senior leadership yet, or they have a level of organizational stability and resourcing most of us would consider fictional.

The Shift in Thinking

So if you can’t “manage” priorities in the traditional sense, what do you do?

The shift is this: stop trying to prevent the juggling. Get better at juggling.

Acknowledge that:

- You will be interrupted. It’s not a bug; it’s a feature of being accessible and accountable.

- You will context-switch. The question is how cleanly you can do it.

- You will have incomplete days. The work will never be “done.”

- Some balls will drop. The skill is choosing which ones can bounce.

This isn’t resignation. It’s realism. And realism is the starting point for actual solutions.

What Experience Teaches You

After a decade of this, here’s what you learn, not from books, but from scar tissue:

1. Protect Recovery Time, Not Focus Time

Everyone talks about blocking “deep work” time. In senior leadership, that’s aspirational at best.

What works better: protect your recovery time.

Block 30 minutes after every high-intensity meeting or context switch. Not to work—to decompress. Take a walk. Grab coffee. Let your brain idle. This isn’t slacking; it’s preventing burnout and maintaining decision quality.

I started blocking “10-minute walks” on my calendar. Sounds silly. Changed everything. My afternoon decisions got notably better.

2. Distinguish Between Decisions and Work

You don’t need two hours for the architecture review. You need 15 minutes to make three key decisions, then delegate the documentation.

Many things on your plate aren’t your tasks—they’re your decisions. Your job is to unblock, provide direction, and move things forward. Separate what needs your judgment from what needs your hands.

I have a rule now: if it needs more than 45 minutes of my continuous focus, someone else should be doing the actual work. My role is to shape it, not build it.

3. Create “Decision Sprints”

Instead of trying to preserve long blocks, batch similar decisions.

Every Monday at 4 PM, I have “decision office hours.” People can book 15-minute slots for anything needing a call: architectural questions, team conflicts, strategy pivots. I’m already in that headspace, so the context-switch tax is minimal.

The rest of the week, unless it’s an emergency, it waits until Monday. This trains the organization, too, they know they’ll get quality time with you, just not always immediately.

4. Master the 5-Minute Triage

When someone comes to your door, you have about 90 seconds to assess: Is this a decision, a delegation, a coaching opportunity, or an actual emergency?

Decision: “Here’s what we’re doing and why. Document it and move forward.”

Delegation: “This is important. Here’s who should own it and what they need from me.”

Coaching: “What have you considered? What would you do? I agree/here’s what I’d add.”

Emergency: Drop everything, but confirm it’s really an emergency first.

Most things people bring to you aren’t emergencies. But they frame them that way because they’re urgent to them. Your triage skill determines whether you get sucked into their urgency or help them solve it themselves.

5. Embrace Asynchronous Leadership

You don’t need to be in every meeting. You don’t need to respond immediately to every message.

Record a 3-minute video explaining your thinking. Write a clear doc. Use async communication to give people what they need without derailing your day.

Some of my best leadership moments now happen at 6 AM before anyone’s online, or at 9 PM when I’m catching up. I’m not always available, but I’m always responsive, just not in real-time.

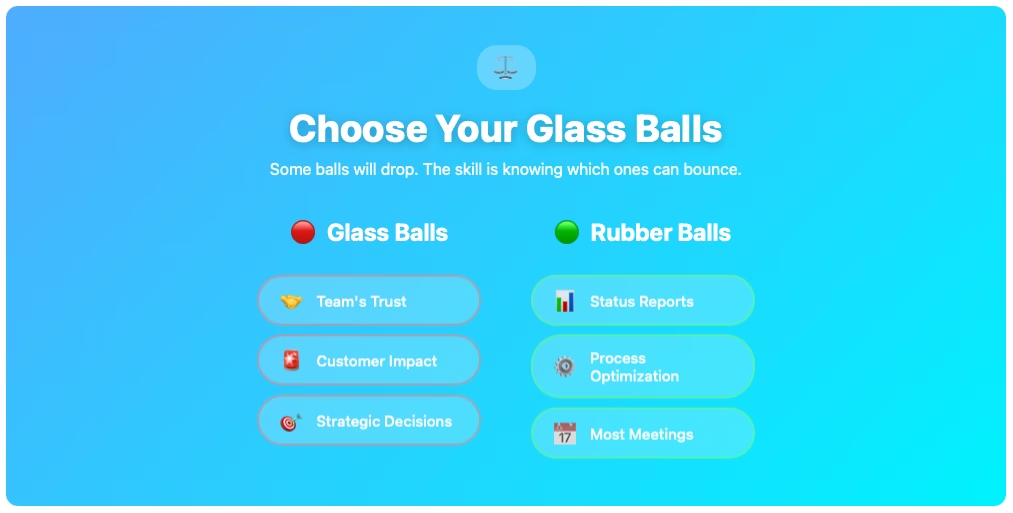

6. Choose Your Glass Balls

There’s an old analogy: some balls are rubber, some are glass. Rubber ones bounce. Glass ones shatter.

You will drop balls. Constantly. The skill is knowing which ones are glass.

Your team’s trust? Glass. Customer-impacting production issues? Glass. Key strategic decisions with irreversible consequences? Glass.

That report your peer asked for? Rubber. Optimizing the sprint process? Rubber. Most meetings? Rubber.

I keep a literal note on my desk: “What’s glass this week?” It changes weekly. It keeps me honest about what actually can’t drop.

Choose Your Glass Balls While Managing Priorities as Engineering Leader

7. Build “Interrupt Capacity” Into Your Day

Stop scheduling yourself at 100%. If your calendar is completely full, you have no capacity to lead.

I now schedule myself at 60-70% max. The rest is “interrupt capacity”, time for the unplanned but inevitable. Some days I use it all. Some days I use it to actually think. Either way, I’m not constantly underwater.

8. Train Your Team to Bring Solutions, Not Just Problems

This one takes time, but it’s force-multiplying.

When someone brings you a problem, ask: “What do you think we should do?” Not in a dismissive way, genuinely asking for their thinking.

Over time, people learn to come prepared. They’ve already thought it through. Your meeting becomes shorter, higher-quality, and more developmental for them.

9. Ruthlessly Eliminate “Fake Work”

A shocking amount of senior leadership time goes to performative work: meetings where nothing gets decided, reports nobody reads, processes that exist because they always have.

Every quarter, I audit my calendar. What meetings can I skip without impact? What updates can be async? What decisions can be pushed down?

I’ve killed entire weekly meetings that had run for years. Nobody noticed.

10. Accept That Some Seasons Are Just Firefighting

During a migration, a reorg, or a scaling crunch, you will firefight. Constantly. That’s not failure—that’s the season you’re in.

Stop beating yourself up for not being strategic during a three-alarm fire. Put the fire out. Stabilize. Then return to strategy.

The key is recognizing when firefighting has become your permanent state. That’s not a juggling problem, that’s a structural problem that needs systemic fixes.

When Juggling Becomes Unsustainable in Managing Priorities as Engineering Leader

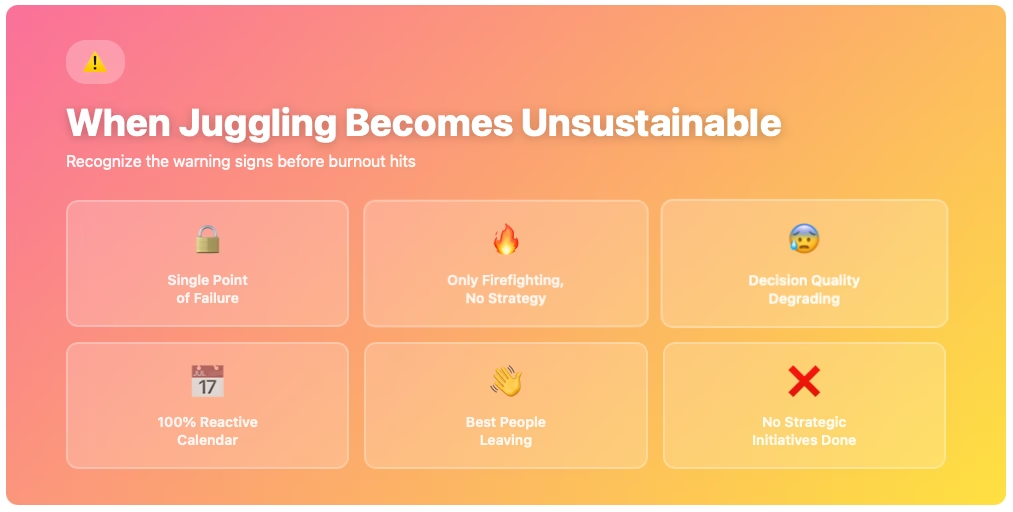

When Juggling Becomes Unsustainable

Here’s the hard part: there’s a difference between juggling as a skill and juggling as a symptom of dysfunction.

You need to recognize when you’ve crossed that line. When the system itself is broken, no amount of personal optimization will fix it.

Warning signs that juggling has become unsustainable:

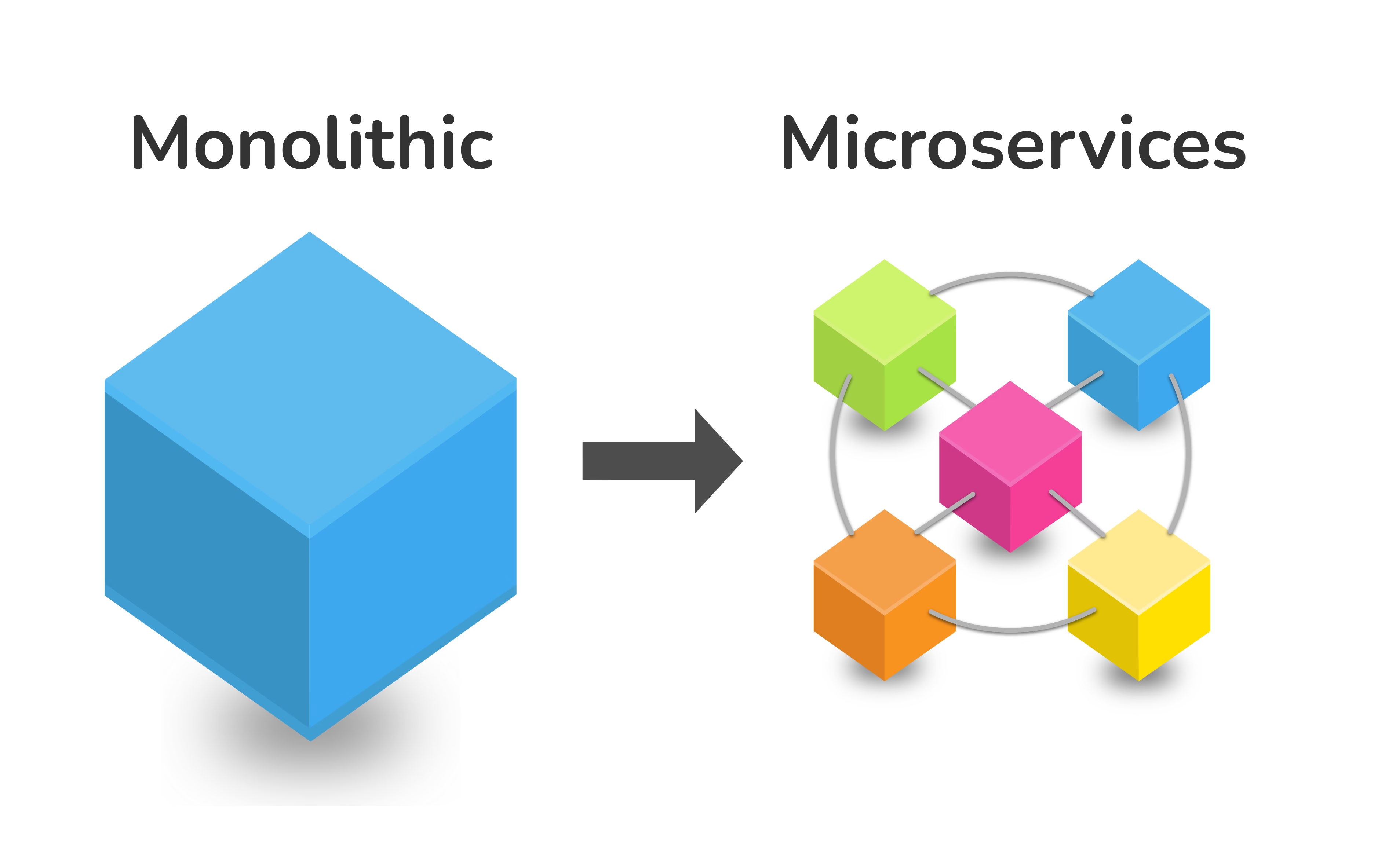

You’re the single point of failure for everything. If you’re personally required for every decision, every escalation, every critical path item—that’s not senior leadership. That’s a bottleneck with a title. You’ve built a system that can’t function without you, which means you’ve built a fragile system.

Your team has stopped bringing you opportunities, only problems. When every conversation is reactive, putting out fires, resolving conflicts, unblocking crises, you’re not leading anymore. You’re triaging. Leadership requires space for proactive thinking, and if that space has completely disappeared, something structural is broken.

You haven’t completed a strategic initiative in months. Tactics are consuming 100% of your time. That architecture review? Still incomplete three weeks later. That hiring strategy? Never got written. That technical debt roadmap? Still just good intentions. When strategy becomes impossible rather than just difficult, the organization is underwater.

Your best people are leaving or disengaging. If your high performers are burning out, going silent in meetings, or quietly interviewing elsewhere, they’re feeling what you’re feeling, but they have an escape hatch. This is the canary in the coal mine. They’re telling you the system isn’t sustainable, even if they’re not saying it directly.

You’re making poor decisions from exhaustion. When you’re constantly operating in firefighting mode, decision quality degrades. You start taking shortcuts. You snap at people who don’t deserve it. You approve things you’d normally push back on just to clear your plate. If you look back at decisions from the past month and cringe, that’s your brain telling you it’s underwater.

Your calendar is 100% reactive. If you couldn’t tell me what you proactively chose to work on this week—if everything was driven by someone else’s emergency, you’re not in control. You’re being controlled by the chaos.

When this happens, juggling better isn’t the answer. Systemic change is:

Push decisions down aggressively. If you’re the decision-maker for everything, you’ve centralized too much. Identify what decisions can be made at lower levels and create frameworks to enable that. Yes, some will be wrong. That’s the cost of scale.

Add leadership capacity. Sometimes you need another senior leader, a strong principal engineer, or an engineering manager to absorb some of the load. If the volume of work genuinely requires more leadership bandwidth, trying to heroically juggle it all yourself isn’t sustainable—it’s martyrdom.

Fix the processes creating the fires. Are you firefighting the same type of incident repeatedly? Is the same organizational conflict pattern recurring? That’s not bad luck, that’s a broken process. Stop treating symptoms and fix root causes, even if it takes time away from other priorities.

Renegotiate scope or timelines. If you’re genuinely underwater, something has to give. Have the hard conversation with your leadership. “Given current capacity and competing priorities, we can deliver X by this date or Y by that date, but not both.” Most leaders respect that honesty more than optimistic commitments that fail.

Audit your obligations. What are you doing that doesn’t actually need to be done? What meetings exist out of habit? What reports are produced but never read? What processes continue because “we’ve always done it this way”? Kill them. Ruthlessly.

The hardest part is admitting that the juggling isn’t sustainable. There’s a voice that says, “Other leaders handle this. Maybe I’m just not good enough.”

That voice is lying.

If you’re constantly underwater despite being competent and experienced, the problem isn’t you, it’s the system. And fixing systems is also part of your job, even when it requires difficult conversations upward and structural changes across the organization.

The Real Skill While Managing Priorities as Engineering Leader

Here’s what a decade teaches you: the skill isn’t managing priorities. It’s managing your cognitive load while juggling them.

You develop a feel for what needs your attention now versus later. You learn to switch contexts cleanly. You build systems that create space even in chaos. You get comfortable with incompleteness.

And some days, you just survive. That’s okay too.

The juggling never stops. But you get better at it. You drop fewer balls. And when you do drop one, you know how to pick it back up.

This is the job. Not the sanitized version in leadership books—the real one. The one where you’re genuinely trying to do right by your team, your customers, and the business, while also staying sane.

You’re not failing because you’re juggling. You’re leading because you’ve learned how.

Leave A Comment